Frozen shoulder

Introduction

Frozen shoulder, medically known as adhesive capsulitis, is a painful and disabling condition characterized by stiffness and restricted movement in the shoulder joint. It primarily affects the glenohumeral joint, where the humeral head fits into the shallow socket of the scapula. The term “frozen shoulder” accurately describes the loss of normal range of motion and the sensation of the shoulder being “stuck” or immobile.

This condition develops gradually and can take months to years to resolve. It often leads to significant discomfort, sleep disturbances, and difficulty performing daily activities such as combing hair, dressing, or reaching overhead.

Anatomy of the Shoulder

The shoulder is one of the most mobile joints in the human body, allowing a wide range of movements such as flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal rotation, and external rotation. It consists of:

- Bones: Humerus, scapula, and clavicle.

- Joint: Glenohumeral joint (ball-and-socket joint).

- Capsule: A loose connective tissue capsule that surrounds the joint and provides stability.

- Synovial membrane: Lines the capsule and produces synovial fluid for lubrication.

- Muscles and tendons: Especially the rotator cuff muscles, which help stabilize and move the joint.

In frozen shoulder, the capsule of the shoulder joint thickens, contracts, and forms adhesions, restricting movement and causing pain.

Definition

Frozen shoulder is defined as a condition of uncertain etiology, characterized by progressive pain and stiffness of the shoulder, leading to a marked limitation of both active and passive movements, without any obvious intrinsic shoulder pathology such as arthritis or rotator cuff tear.

Epidemiology

- It affects 2–5% of the general population.

- More common in women than men (female-to-male ratio approximately 2:1).

- Most commonly occurs between the ages of 40 and 60 years.

- The non-dominant shoulder is often affected, though in some cases both shoulders may become involved sequentially.

- It is particularly common in people with diabetes mellitus, with an incidence up to 10–20%.

Causes and Risk Factors

Frozen shoulder can be classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary depending on the underlying cause.

1. Primary (Idiopathic) Frozen Shoulder

The exact cause is unknown, but it may be related to inflammation or autoimmune response leading to fibrosis of the capsule.

2. Secondary Frozen Shoulder

Occurs due to another underlying condition or event that limits shoulder mobility. Common causes include:

- Post-surgery or immobilization: After fracture, shoulder surgery, or prolonged immobilization.

- Systemic diseases: Diabetes mellitus, thyroid disorders (hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism), cardiovascular disease, and Parkinson’s disease.

- Trauma: Minor shoulder injuries that discourage movement, leading to stiffness.

Risk Factors

- Age (40–60 years)

- Female gender

- Diabetes or thyroid disease

- Shoulder injury or surgery

- Prolonged immobilization (e.g., after fracture)

- Autoimmune conditions

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism is not fully understood, but frozen shoulder is believed to occur due to:

- Inflammation of the synovial lining of the shoulder capsule.

- Fibrosis and thickening of the joint capsule.

- Adhesion formation between the capsule and the humeral head.

- Loss of joint volume (normally 15–20 mL, reduced to 5–10 mL in frozen shoulder).

This leads to pain, restriction of movement, and gradual loss of function.

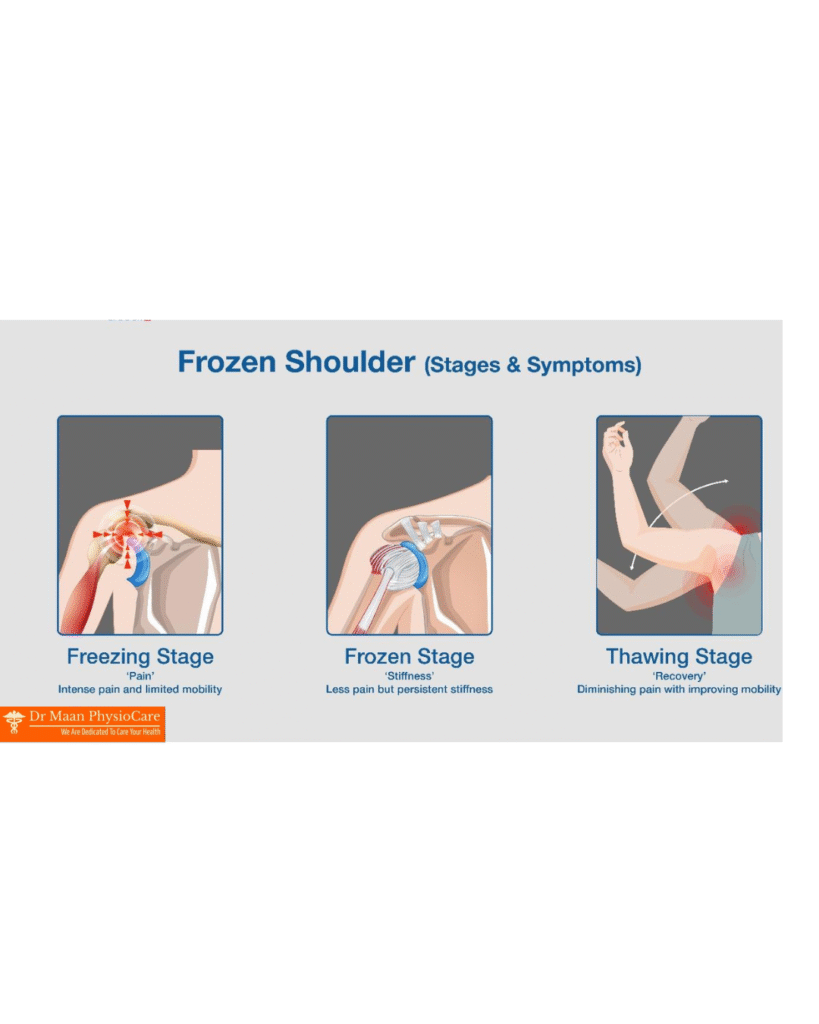

Stages of Frozen Shoulder

Frozen shoulder progresses through three overlapping stages, each lasting several months:

1. Freezing Stage (Painful Stage)

- Duration: 2–9 months.

- Pain is the predominant symptom, especially at night or with movement.

- Gradual loss of shoulder range of motion.

- Inflammation of the capsule is prominent.

2. Frozen Stage (Adhesive Stage)

- Duration: 4–12 months.

- Pain may reduce, but stiffness becomes severe.

- Range of motion is markedly restricted in all directions.

- Daily activities become difficult due to limited mobility.

3. Thawing Stage (Recovery Stage)

- Duration: 6–24 months.

- Gradual improvement in shoulder movement and function.

- Pain continues to decrease.

- Capsule slowly regains its elasticity.

Total duration of the condition may range from 1 to 3 years in most cases.

Clinical Features

Symptoms

- Gradual onset of pain and stiffness.

- Dull, aching pain localized to the shoulder and sometimes radiating to the upper arm.

- Night pain, making it difficult to sleep on the affected side.

- Difficulty with overhead activities, such as combing hair, dressing, or reaching behind the back.

Signs

- Restriction of both active and passive movements, particularly external rotation.

- Capsular pattern of restriction: External rotation > abduction > internal rotation.

- Tenderness over the deltoid region or anterior shoulder.

- No significant muscle wasting initially.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is mainly clinical, based on history and physical examination.

1. Clinical Examination

- Observation: No swelling or deformity.

- Palpation: Tenderness over the anterior shoulder joint.

- Range of Motion: Both active and passive movements restricted.

- Capsular pattern: Loss of external rotation most marked.

2. Investigations

- X-ray: Usually normal but may show osteopenia due to disuse.

- MRI or Ultrasound: May reveal thickened capsule, coracohumeral ligament thickening, or decreased joint volume.

- Blood tests: To rule out underlying diseases like diabetes or thyroid disorders.

Frozen shoulder is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning other causes of shoulder stiffness (e.g., arthritis, rotator cuff tear) must be ruled out.

Differential Diagnosis

Conditions that may mimic frozen shoulder include:

- Rotator cuff tear

- Subacromial bursitis

- Glenohumeral arthritis

- Cervical spondylosis

- Suprascapular nerve entrapment

Management

The primary goals of treatment are:

- To reduce pain

- To restore range of motion

- To improve function

Management can be divided into conservative (non-surgical) and surgical approaches.

1. Conservative Treatment

a. Patient Education

- Reassure the patient that the condition is self-limiting.

- Explain the stages and expected duration.

- Encourage gentle movement and avoidance of prolonged immobilization.

b. Medication

- NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs): For pain relief and inflammation.

- Corticosteroid injections: Intra-articular steroid injections can reduce inflammation and pain, especially in the early (freezing) stage.

c. Physiotherapy

This is the mainstay of treatment.

Goals of Physiotherapy:

- Pain relief

- Restoration of joint mobility

- Prevention of muscle wasting

- Improvement in function

Physiotherapy Techniques:

- Hot Packs or Ultrasound Therapy

- Helps reduce pain and increase tissue elasticity before stretching.

- Pendulum Exercises

- Gentle swinging of the arm to promote joint mobility.

- Range of Motion Exercises

- Passive, active-assisted, and active exercises for flexion, abduction, and rotation.

- Capsular Stretching

- Specific stretches targeting the tight capsule.

- Mobilization Techniques (Maitland/Kaltenborn)

- Grade I and II for pain relief; Grade III and IV for improving mobility.

- Strengthening Exercises

- Once mobility improves, strengthen rotator cuff and scapular muscles.

- Posture Correction

- To maintain proper shoulder mechanics.

d. Modalities

- TENS (Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation): For pain management.

- Ultrasound Therapy or SWD (Short Wave Diathermy): To improve blood flow and tissue healing.

e. Home Exercise Program

- Regular home exercises are crucial for long-term recovery.

2. Surgical Treatment

Indicated only if conservative management fails after 6–12 months.

Options:

- Manipulation Under Anesthesia (MUA):

- The surgeon moves the shoulder through its full range to break adhesions while the patient is under anesthesia.

- Risks: Fracture, dislocation, or tendon injury.

- Arthroscopic Capsular Release:

- Minimally invasive surgery to cut tight capsule areas and restore motion.

- Often followed by aggressive physiotherapy.

Prognosis

- Frozen shoulder is usually self-limiting and resolves over 1–3 years.

- Most patients regain 90% of shoulder movement.

- However, some stiffness may persist, especially in diabetic patients.

- Early diagnosis and proper physiotherapy lead to faster recovery.

Complications

- Persistent stiffness and reduced range of motion.

- Shoulder weakness or atrophy due to disuse.

- Recurrence in the opposite shoulder.

- In rare cases, chronic pain.

Prevention

While not always preventable, risk can be reduced by:

- Early mobilization after injury or surgery.

- Regular shoulder exercises to maintain flexibility.

- Good diabetes and thyroid control.

- Avoiding prolonged immobilization of the arm.

Leave a Reply